壬午年春(1946年),米南阳生於京师,家传书艺。自宋代始,祖米芾,以墨香传家,血脉所继于传统。其父米友文,京中名医,严以教子,使七子女皆泳於文史哲之海。自幼执笔,五岁始,南阳已登书法求道之路。童年沐于诗书画剑,勤苦充实,青春时日则色彩斑斓。

In the spring of Renwu year (1946), Mi Nanyang was born in the capital, inheriting the art of calligraphy from his family. Since the Song dynasty, his ancestor Mi Fu had passed down the art through the fragrance of ink, a tradition continued in his lineage. His father, Mi Youwen, a renowned physician in the capital, rigorously educated his seven children in literature, history, and philosophy, immersing them in the ocean of scholarly pursuits. From a young age, holding a brush at the age of five, Nanyang embarked on the path of seeking the art of calligraphy. His childhood, bathed in poetry, books, painting, and swordsmanship, was diligent and colorful.

米家子,书法自然成才,字字珠玑,历代学问,融会贯通。自临摹至独创,自颜真卿之刚劲至柳公权之飘逸,融历代书风于一炉,酿成米氏一格。南阳知深,书之妙处,不在技巧,乃在修养。父语曰:“此即‘字内功’也。”诗词、歌赋、曲艺、武术,皆书法之肌肉;经史子集,则其魂魄。文化精粹汇聚,书法乃能展其深厚艺境,载吾民性灵归依也。

The descendants of the Mi family naturally excelled in calligraphy, each character crafted as a gem, blending the wisdom of generations. From copying to creating original works, from the robustness of Yan Zhenqing to the grace of Liu Gongquan, Nanyang integrated the styles of all ages into his own unique Mi style. He understood deeply that the essence of calligraphy lies not in technique but in cultivation. His father said, "This is the 'inner power' of calligraphy." Poetry, essays, opera, martial arts—all are the muscles of calligraphy; theics and historical texts are its soul. When the essence of culture is amalgamated, calligraphy can then express the profound artistic realm and embody the spirit of our people.

父严如师,院中教武,严格甚。少年南阳,小立砖上,翻身三十,不出界限,逾矩则受棒惩。红木镇尺,成忆中噩梦,朝背诵,暮复习,严苛磨砺,练其过目不忘。岁月流转,南阳能畅背《汤头歌》,论京剧之精妙,展行云流水之书法。彼时,样板戏流行,南阳亦展才华于舞台,传统文化之精髓,深植其生命。

As stern as a teacher, his father disciplined them in martial arts in the courtyard. As a youth, Nanyang stood on small bricks, somersaulting thirty times without stepping off, facing punishment if he did. The redwood ruler became a nightmare in his memories; reciting in the morning and reviewing at night, the rigorous challenges honed his ability to remember effortlessly. Over time, Nanyang could recite "Tang Tou Ge" fluently, discuss the nuances of Beijing opera with gestures flowing like water. During the era when model operas were popular, Nanyang also showcased his talent on stage, embedding the essence of traditional culture deeply within his life.

壬辰岁于京师,米南阳十八春,步入友谊宾馆,主青年之旗。天资独秀,如群星中一耀眼新秀。适值变局,大潮卷之,被逐至塞外新疆,沉矿井之深渊,劳役挖煤。历七载,十一度濒死,身遍伤痕,一度被弃后山,幸得乡亲携手,得归于生之门。瞬息间,沙尘葬十二伙伴,此情此景,铭记心间,不复触及。然艺术与信仰,如翼之光,照其得出黑渊。尘世岁月,未尝弃文墨,无纸笔,则以指代笔,以血为墨,任何空白,皆成其练字之所。

In the spring of Renchen year, at eighteen, Nanyang stepped into the Friendship Hotel, leading the youth as a shining new star. Facing drastic changes, he was exiled to the far reaches of Xinjiang, thrown into the abyss of coal mines to labor. Over seven years, he faced death eleven times, once left for dead in the mountains, saved by fellow villagers from the brink of death. The dust storms that buried twelve of his companions left an indelible mark on his heart, never to be touched again. Yet, art and faith, like wings of light, guided him out of the dark abyss. Throughout these dusty years, he never abandoned pen and ink. Lacking paper, he used his fingers as brushes and his blood as ink, turning every blank space into a canvas for practice.

乙未春,命运神佑,周总理指示,重获自由。返京,祖声若冷风扑面,言其荒废岁月。然陈仰山一问,如春雷,唤醒沉睡之心:“愿复七年否?”南阳坚决应允。遂闭门谢客,困居六平米之室,重始练习,书为友,笔为伴,以学问坚持,重铸生命。岁月如梭,七年后,步出于世,智慧已成。丁酉春,改革之风起,五芳斋匾额,乃挥毫之地。三字入墨,融入生命之厚重与深思。父亲三至王府井,赞其成就,暖其心田。继之,匾求者众,念父训,不为名利所动。于繁华处,退一步,求清静,以静制动,以退求进,又历七载磨砺,更明澈,追求艺术之更高境界。每于案前,执笔立,世间杂音顿消,唯余与神对话之诚。七十年书艺路,亲历每步,从铺纸至封印,每一环皆为对艺术之敬。研墨非但为书,更为冥想,潜心寻觅,思时间之流动与空间之凝固。

In the spring of Yiwei, by divine providence, Premier Zhou Enlai ordered his release. Returning to the capital, his grandfather's harsh words about wasted years hit him like a cold wind. However, a question from the elderly Chen Yangshan awakened his dormant spirit, "Do you wish to reclaim those seven years?" Nanyang's firm answer led him to shut himself away, confining himself to a tiny six-square-meter room, restarting his practice, making books and pens his companions, and painstakingly reconstructing his life. As time passed, emerging after another seven years, Nanyang had matured in wisdom. In the spring of Dingyou, as the winds of reform began to blow, the refurbishment of the "Wufangzhai" plaque became his stage for a display of calligraphy. The three characters he wrote infused with the depth and thought of life. His father, visiting Wangfujing three times to see his son’s work, finally expressed his approval, warming Nanyang's heart. Subsequently, although many sought his services for plaques, mindful of his father's teachings, he declined, choosing seclusion over fame. Another seven years of refinement clarified his aspirations, aiming for ever higher realms of art. Every time he stood at his desk, the world's noise faded away, leaving only a sincere dialogue with the divine. Through seventy years of calligraphy, Nanyang personally experienced each step from laying out the paper to the final seal, each act a reverent tribute to art. Grinding ink was more than preparation; it was a meditation, a search for the flowing of time and the solidification of space within the silence.

自古书法,非徒技艺之展也,更乃心手相悟之途。米南阳者,笔端携风雷,妙手生花,以书为鉴,照见心迹。彼深契此道,每逢落笔,即是过己之炼,超然之旅也。艺途漫漫,革新不辍,乃其所以绵延不息之本。南阳持之以恒,掘题材之奥,释文字之新义,常存心一则:温故知新。每遇新诗,必先研究透彻,背诵精炼,深纳其神髓,然后才随笔引思,使墨流中既见丹青,亦觉诗意灵动。于己所铸之诗词,更倾尽心血,以笔传情,书以载道,使之成一体,显自我艺术之语言。

The art of calligraphy is not merely a display of skill but a journey of the heart and hand in communion. Mi Nanyang, with his brush infused with dynamism and his hands capable of bringing life, used calligraphy as a mirror to reflect the soul. Deeply rooted in this philosophy, each stroke he made was a refinement of self, an elevating journey. The path of art is long, and only through ceaseless innovation can it endure. Nanyang persisted, delving into the depths of themes and unveiling new interpretations of text, ever adhering to the principle: To understand the old and know the new. Each time he encountered a new poem, he would study it thoroughly, memorize it completely, and absorb its essence before letting his brush follow the flow of thought, allowing the ink to reveal not only vibrant hues but also the spirit and poetry within. For his own poetry and essays, he poured out his heart, using the brush to convey emotion and embody philosophy, achieving a unity that expressed his personal artistic language.

南阳好交启功先生,彼此以艺术信仰为纽带,情谊益坚。偶于访中,见启公拣择题词甚严,拒人平庸之联,此非骄也,实其守艺自重之表现。启公有言在焉:“书家当存词汇于腹中。”南阳好学不倦,受费新我先生困境中创新之感,试以左手挥墨,探索书艺新境界。左笔之下,别开生面,呈异样风采。作《虎跃龙腾》一帧,左右笔法相间,形成视觉与感觉之和谐美感,令观者神移。值京师首都机场新道将启,启功推南阳题书,此赞其深厚书艺与创新能力也。南阳所题“国门第一路”,既树书法之精粹,又展现时代之风采,大字如历史厚重,现代感并融,桥梁也,贯古今以通。启功评其书有时代感之锐,南阳亦以古今融合为志,传承开创并重,非徒技艺,更显文化意蕴。南阳自谓:“守传统之根基,显时代之气象,展个性之风采,三者俱不可或缺。”

Nanyang valued his friendship with Qi Gong, bonded by their belief in art, strengthening their connection. During an impromptu visit, he observed Qi Gong's stringent selection of phrases for calligraphy, rejecting mundane couplets not out of arrogance but as a display of artistic integrity. Qi Gong once noted, "A true calligrapher should fill his belly with words." Nanyang's insatiable curiosity was sparked by Fei Xinwo's innovative spirit, which led him to experiment with writing with his left hand, seeking new dimensions in calligraphy. His left-handed strokes brought a fresh perspective, displaying unique charm. In his work "Tiger Leaps and Dragon Soars," he alternated between left and right-hand strokes, creating a harmony of visual and tactile sensations that captivated viewers. When the new highway to Beijing Capital Airport was about to be inaugurated, Qi Gong recommended Nanyang for the inscription task, acknowledging his profound skill and innovative capabilities. Nanyang's inscription "First Road of the Nation's Gate" not only demonstrated his solid foundation in calligraphy but also showcased his willingness to innovate and express the spirit of the times. These five characters, embodying both historical depth and a modern sensibility, served as a bridge linking past and present. Qi Gong praised Nanyang's calligraphy for its strong sense of the contemporary, an accolade that Nanyang cherished as he sought to blend ancient techniques with modern cultural expressions, striving for continuity and innovation, not merely showcasing skill but also enriching cultural discourse. Nanyang himself stated, "One must uphold the foundation of tradition, display the characteristics of the era, and express one's personal style; these three are indispensable."

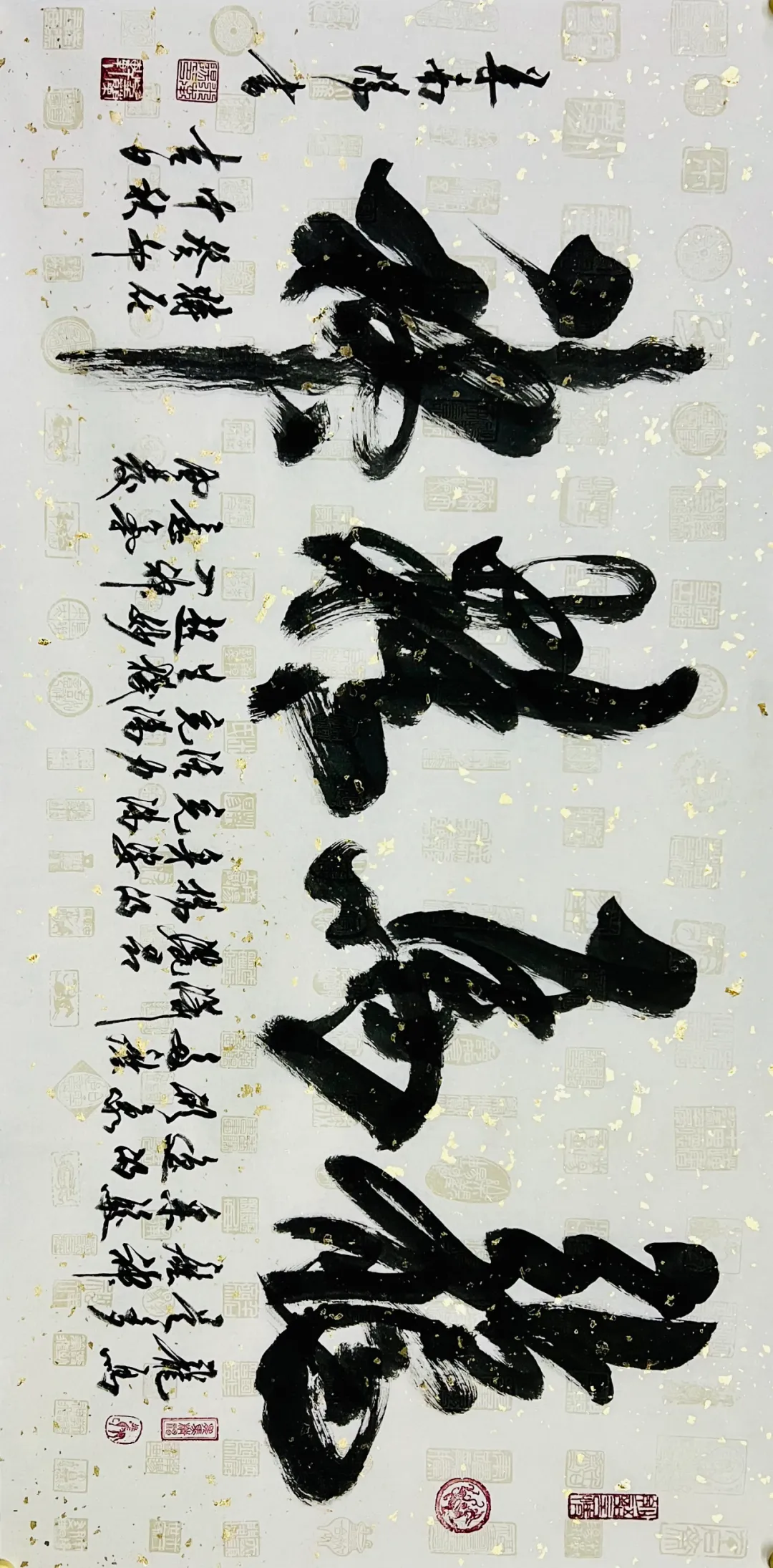

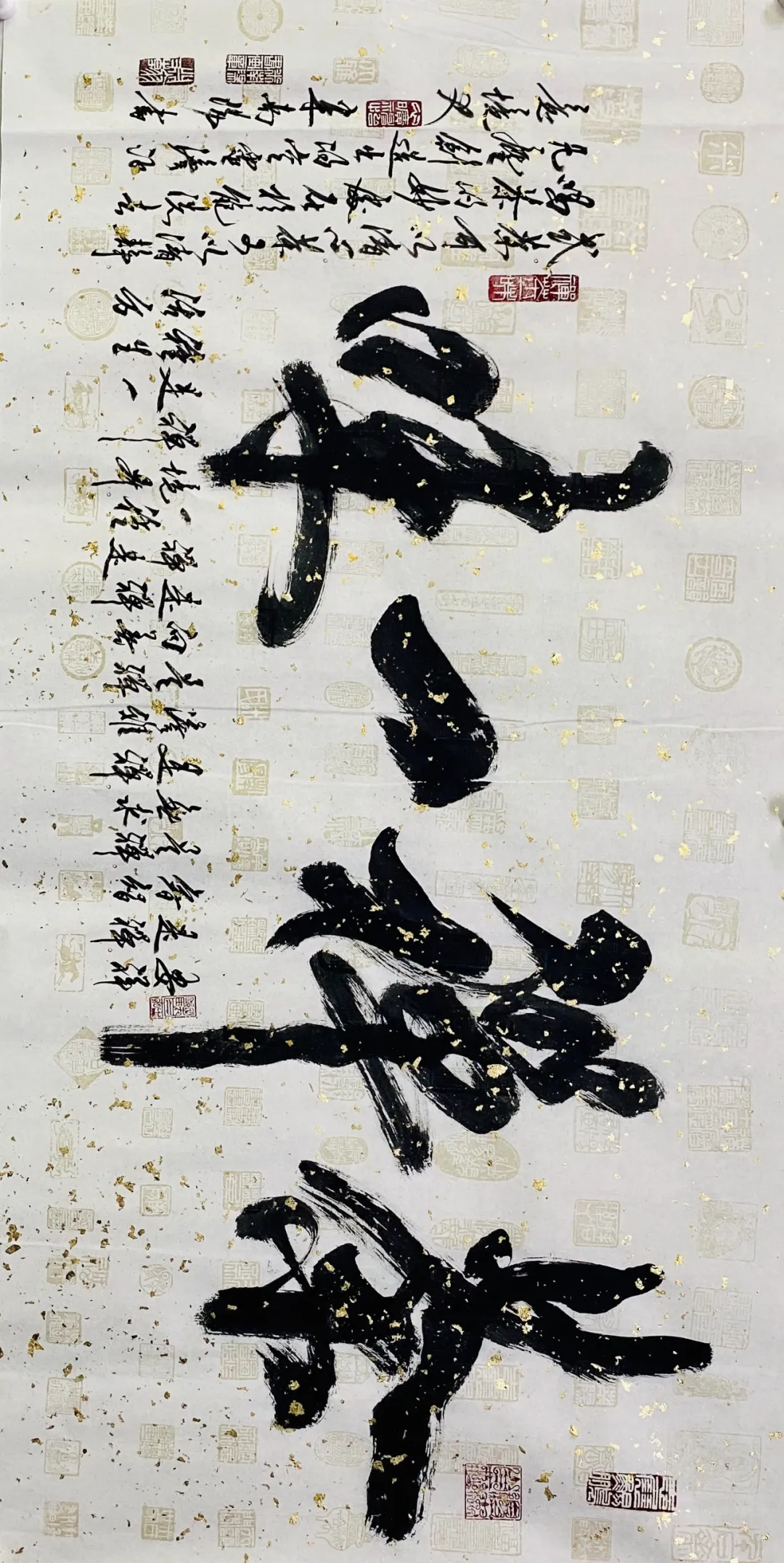

米南阳之书道,自由与革新齐驱,步自隽永。笔法自由,一挥而就,其笔每落,皆是求索自由之矢志,彰显无羁之境界。要言南阳书风,莫过于“弯”字一彰。民间流传曰:““启功之杆儿,溥杰之尖儿,舒同之圈儿,米南阳之弯儿”此二十字,言当世四家书风。其中南阳“弯儿”之神韵,笔触宛若春风拂绸,波涛滔滔,烟云缥缈,乃自在逍遥之灵魂笔墨。

Nanyang's journey in art, paralleling freedom and innovation, follows a path of profound distinction. His strokes are free and executed with ease, each one a testament to his quest for freedom, showcasing an unbound realm. When discussing Nanyang's style, one must mention the "bend," a feature that has become emblematic of his approach. The saying goes, "Qi Gong's shaft, Pu Jie's tip, Shu Tong's circle, and Nanyang's bend." This description, encapsulating the distinctive brushwork of four contemporary masters from Beijing, highlights Nanyang's "bend" as particularly evocative. His strokes, whether sweeping like the spring breeze across silk ribbons, surging like mighty rivers, or meandering like misty peaks, are all infused with an effortless grace that captivates and enchants. These curves not only reveal his natural expression of emotions but also his profound pursuit of beauty, resembling the free-spirited wanderings of a scholar, engaging in a deep dialogue with the soul.

逾时,父忧其书业或致泛滥,令其静候艺成。年华渐逝,南阳书风愈发锋芒毕露,如沉香之渐燃,氤氲而上。其笔触既厚重而不失灵动,所书匾额,遂成载墨之舟,携带深邃意蕴,行于京师街头,从人民大会堂之咏梅厅至钓鱼台,字字皆是古卷延展,贯穿繁华与宁静。南阳之书,不拘一格,流于平面,自《中国计算机报》至国之电视台,乃至家喻户晓之影视剧名,书迹皆入人心。《米老鼠和唐老鸭》之名,出自南阳一时之灵感,示书法于现世文化之新采。议集匾额以展,南阳始于“每日一匾”于友圈,作品众多,远超日计,遂改“每日一版”,昭示其艺之广,流传之深。南阳所重,尤喜深文大义之作,非金可赎,乃长年累月之修为,艺术瞬间之天成。

Over time, his father's concern that his art might become too prolific prompted Nanyang to pause and reflect, waiting for his skills to mature. As the years passed, his style became increasingly sharp and incisive, like agarwood slowly igniting, its fragrance filling the air. His brushwork, both robust and agile, enabled his inscribed plaques to become vessels carrying the depth of his ink, traveling across the streets of the capital. From the People's Great Hall's Mei Pavilion to the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse, his characters stretch across scrolls, bridging bustling and tranquil scenes. Nanyang's calligraphy transcends conventional boundaries, appearing everywhere from the "China Computer Newspaper" to national television channel logos, and even in the titles of well-known television dramas, embedding his strokes deep into the public's heart. The name for the animated series "Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck" sprang from his spontaneous inspiration, showcasing the freshness of calligraphy in contemporary culture. Considering an exhibition, Nanyang initially shared a "Plaque a Day" on social media. Given the vast number of works, exceeding daily posts, he switched to "Page a Day," illustrating the breadth of his art and the depth of its reach. Among his numerous works, Nanyang favors those born from deep cultural cultivation—like the priceless "Harmony" character in the Hong Kong market, its single stroke elegantly resembling a peace dove, embodying tranquility and inclusiveness, demonstrating the unity of form and spirit in calligraphy. This character, transcending mere writing, is a divine gift of art. Similarly, the "Buddha" character with its hidden image of Guanyin and the "Blessing" character depicting an elderly couple, both reveal the cultural depth and artistic sensitivity in Nanyang's work. These pieces are invaluable, the result of years of practice and insight, unique artistic moments that cannot be replicated.

南阳亦工绘画,笔下山水人物,如诗如梦,风格独出,每一笔画,皆彰其深厚学养。画中有诗,诗中有画,加以自制印章,诗书画印交融,内外相成。南阳自幼习得诸多技艺,融入生命,情至京胡,以之为书前之暖身;酷爱京剧,能即席展金裘之别;亦爱相声,常与名演共酌佳句;又嗜美食,将常食化为盛宴,菜名如画,使品者于品味间亦能感如诗之美。如是艺术之路,自由与创新并行,南阳之笔,逐自由而行,每一笔画,皆情感之自然流露,美之探求也。

Nanyang is also skilled in painting, with his landscapes and figures exuding a poetic and dreamlike quality, each stroke manifesting his profound scholarly background. His paintings incorporate poetry, and with his custom-made seals, he achieves a synthesis of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving, intertwining form and content. From a young age, Nanyang mastered various traditional arts, integrating them into his life. He cherishes the Jinghu, using it as a warm-up for calligraphy; he adores Beijing opera, capable of impromptu performances; he enjoys comic dialogue, often exchanging witty verses with famous actors; and he is a gourmet, transforming ordinary ingredients into culinary masterpieces, with dish names as evocative as paintings, allowing diners to experience poetic beauty through taste. His artistic path, where freedom and innovation walk hand in hand, sees his brush moving freely, each stroke naturally expressing emotion, a quest for beauty.

帝都紫禁,岁序流转,瞩目华夏之盛世,鉴古今之繁荣兴衰。南阳书道,如古邦新韵并蓄之城,倾力对话古今,以笔墨为桥,合承创之美,于悠悠书艺,展博大胸襟与时代风情。

Amidst the cyclical changes of the Forbidden City, witnessing the flourishing of China's golden ages, Nanyang's calligraphy practice is like this ancient yet vibrant city, tirelessly conversing with both antiquity and modernity, using brush and ink to bridge traditional and contemporary realms, harmoniously blending the old and the new, allowing calligraphy, this enduring Chinese art, to exhibit immense inclusivity and a distinct sense of the times.

责任编辑:苗君